Methodology

To achieve our objectives, and to address as systematically and comprehensively as possible all of the factors discussed above, ARTIS requires cross-cutting disciplines and integrating methodologies from diverse fields of research. Indeed, this is the strength and the defining principle of our ARTIS consortium. We bring together a number of research groups that have themselves often defined and, in many cases designed, the state-of-the art approaches for investigating, contextualizing, and applying empirical data regarding art experience. Below, we briefly walk through the main approaches that will empower this project:

- Establishing an empirical baseline definition of the types, the nature, and the implications of our interactions with art—including transformation

- Top-down identification of “transformative” artworks or those addressing societal challenges— do these actually produce meaningful results?

- Beyond surveys to a multi-perspective nuanced understanding of art experience

- Experience sampling and tracking of art experiences in everyday life

- Assessment of the work of artists; Social, cultural, and political aspects of arts engagement

- Theoretical and art-historical embedding and connections of empirical approaches to wider discussions on the arts and science

- Experiments or interventions with participants

- Co-creation and co-experimentation with artists

- Inclusion of Marginalized and Disengaged groups

- Policy investigation and production

Establishing an empirical baseline definition of the types, the nature, and the implications of our interactions with art—including transformation

Establishing an empirical baseline definition of the types, the nature, and the implications of our interactions with art—including transformation

Our unique methodology begins with a cutting-edge approach to systematically assess the varieties and nature of art experience. The first ARTIS objective necessitates the capturing of empirical data on encountering art, and more importantly, requires a systematic, theoretically-grounded method for anticipating and quantifying interactions in a range of settings. This is coupled with our ultimate aim of identifying and assessing specifically those encounters that are transformative or that, in some way, make an impact on a viewer, uniting these with a consideration of measurable changes that engaging art might engender.

In order to achieve these aims, we will build from a series of methods and pilot studies created by UNIVIE. First, we specifically assess and quantify the nature of art experiences in general (considering both art as it is encountered in the museum or gallery, WP2, and on the street or in public urban settings, WP3). This necessary step is already begun by our empirical aesthetic partners, however will be greatly expanded within the scope of the ARTIS project. This step is itself required for further discussions around the aims of this project, creating a map of “art engagement” and specific experience types, upon which we can place our further interventions, assessments, and policy planning. We achieve this using a state- of-the-art psychological model and a self-report method for onsite art study, matched with advanced statistical modeling of the resulting shared art experiences.

Theoretical Model

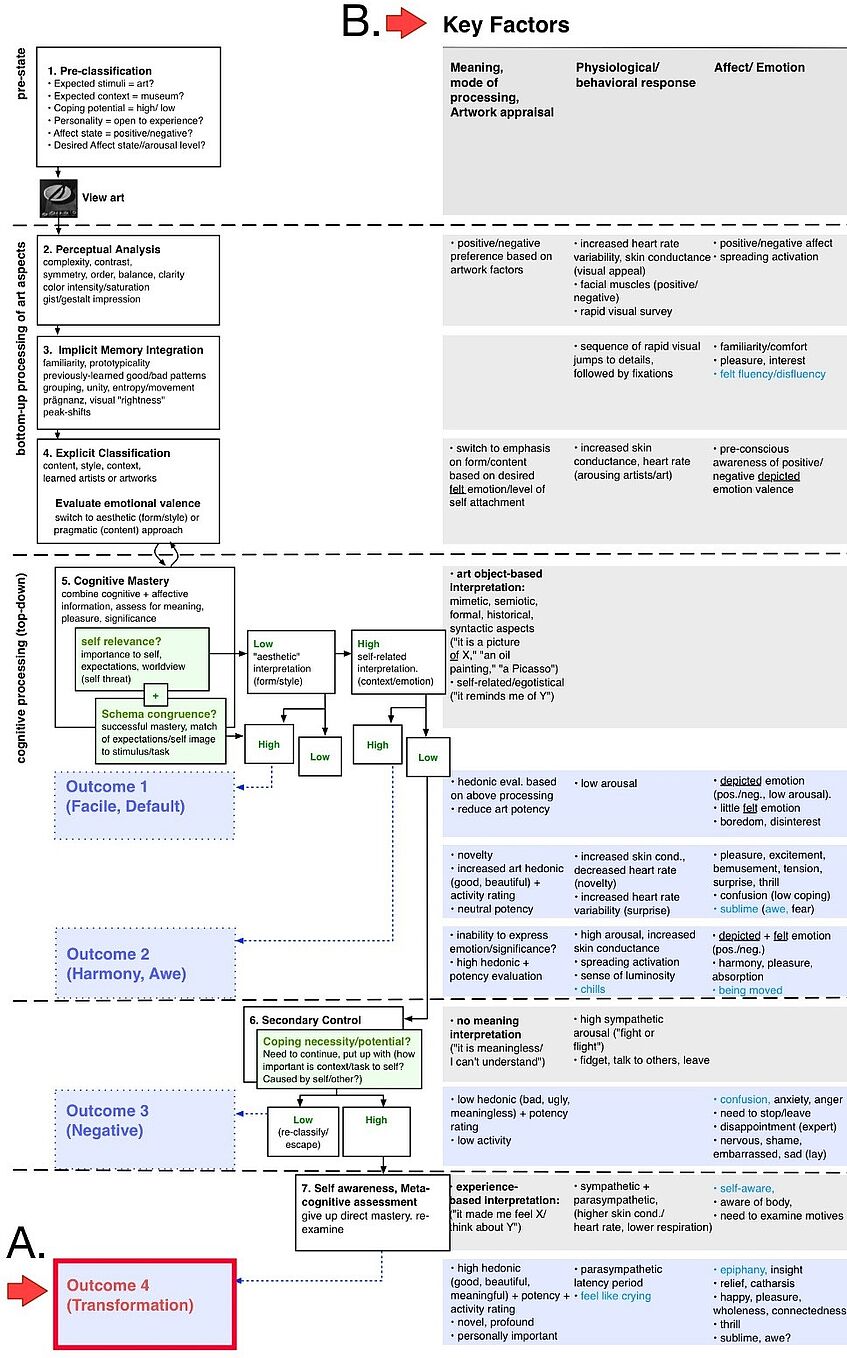

The main base of our empirical assessments involves a model for art experience (the Vienna Integrated Model of Art Perception, VIMAP, Pelowski et al., 2017). This model again (and its earlier iterations, Pelowski & Akiba, 2011) is considered the most comprehensive attempt to organize and explain art responses (Kuiken & Jacobs, 2017). It is also the first to specifically articulate, within this frame, transformative experiences or specific cognitive or behavioral changes as a distinct type of art engagement.

The model follows a perspective of cognitive psychology, which argues that the nature of evaluations, our emotional and physiological responses, etc., can be seen as the end result of a cognitive progression with map-able stages. As shown in Figure 3, the model specifies seven steps, encompassing bottom-up processing of formal artwork factors, top-down influence from memory and training, followed by integration of information channels leading to an initial affective and evaluative response, and also secondary, more viewer- centered stages in which an individual may respond to, modulate, or give further meaning to their experience.

The model further integrates these stages with specific broad varieties of engaging art (‘Outcomes,’ see blue boxes Fig. 3) and hypotheses for physiological, emotional, evaluative, cognitive, as well as brain activation factors argued to arise within, and partially define, each experience type. These include: (1) a generally default or mundane reaction (identified by both high congruence and low tie to the self), with generally short viewing duration, little emotion, and appraisals based on immediate artwork- processing stages; (2) cases of both high schema congruence with higher self-relevance, leading to particular powerful and engaging experiences, in which some element—the artwork form, felt emotion— resonates with a viewer and ushers in a period of harmony, awe, wonder; (3) a quite negative result, stemming from low congruence with high-self relevance, thus felt as a direct threat or challenge, and resulting attempts to extricate oneself by leaving, downgrading the artwork or the setting’s (i.e., a museum’s) importance, with reported negative emotions, or (4) similar cases in which individuals experience initial difficulty and challenge, but where they rather continue to engage an artwork, leading to a period of self-awareness, reflection, and eventual

“transformation” in some aspect (expectations, perceptions, concepts, depending) brought to the work. Depending on the level of prior self-importance, these changes can of course run from basic experiences of novelty or interest to cathartic release, and feelings of growth and insight, which again might be particularly intriguing targets for this project or societal change through art

Fig 3. Vienna Integrated Model of types of art experience and especially transformative variety. (Pelowski, Leder, et al., 2017). A. Transformative Outcome. B. Factors that may be used to assess art experience in self-report or other investigations

Behavioral survey-based ecologically valid assessment

To then assess art experience and identify the distinct nature for a particular individual, the model will be paired with a paradigm, also designed by UNIVIE, to capture and later quantify the above types as they occur in a natural engagement with art. This involves the use of a selection of those specific factors (emotions, appraisals, aspects of understanding, suggested from the right columns of the model). These are assessed via a self-report survey, administered after an experience with a work of art, whereby individuals can report on the incidence and magnitude of each factor (using Likert-type scales).

The survey is also embedded within a carefully designed procedure for an ecologically valid assessment: a specific work of art or related art series (i.e., by the same artist) are selected and set apart within one gallery space or other defined setting, minimizing as much as possible other conflating elements (other artworks, labels, etc.). Participants are asked to view the art in whatever manner and for whatever duration is desired, and then to report via the survey on their experience. By assessing the combination of reported factors, this provides a robust means of both identifying a specific outcome and of creating a map of the global art experience, while maintaining, as much as possible, a “natural” art engagement without intrusion from researchers and within the ambience of the wider (i.e., and art museum/street) setting.

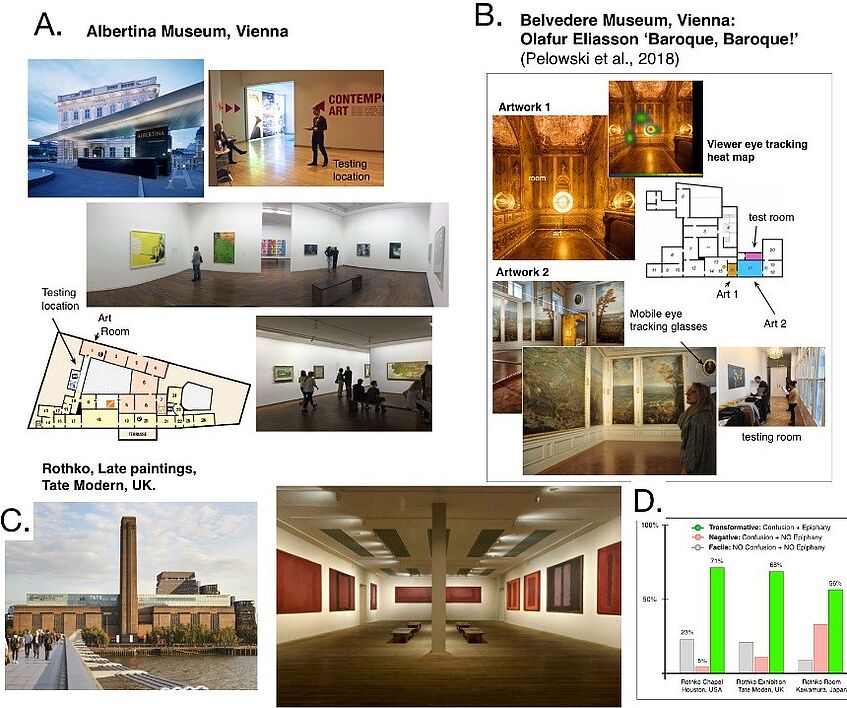

The model and survey methodology have shown high promise in a number of preliminary studies conducted at art museums and galleries throughout the U.S., Japan, and Europe, including the Tate Modern, London, the Albertina in Austria, as well as the Belvedere in collaboration with artworks by Olafur Eliasson (Pelowski, 2015; Pelowski et al., 2018, in prep; Pelowski et al., 2012, 2014; see also Pelowski et al., 2017 for best practice suggestions for museum research). Results, have shown promising ability to separate viewers, based on a few main factors, into experience types and to identify particularly transformative art (e.g., documenting this, and tying transformation to specific insight and positive emotions with certain abstract and representational art). Equally important, outcomes and responses also show consistency across viewers and art types, suggesting a basis for important cross-artwork comparison. The methodology has also been applied in collaboration with curators (Pelowski et al., 2014, e.g., working at a museum in Japan), using identified outcomes and assessment of movement patterns and contextual factors to suggest changes in gallery design/art presentation to increase likelihood of positive or transformative experiences. It has also been employed to assess interactions with art as encountered in public streets (Mitschke, Leder et al., 2017).

Left: Ecological valid assessment

Fig 4. Previous onsite museum studies and paradigms. A. Albertina Museum, Vienna. B. Belvedere museum, Vienna. C. Tate Modern, London. D. identification of transformative experience with same art in three cultures.

Right: Network Model

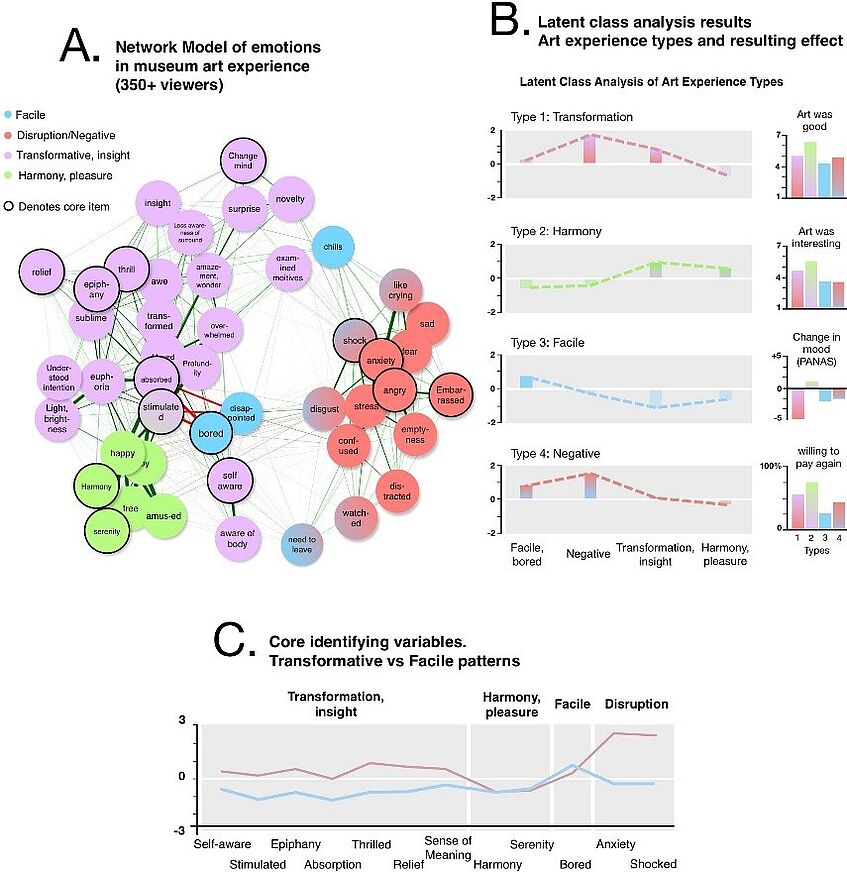

Fig 5. Example of pilot Network Model and Latent class analysis. A. general art viewing emotional/cognitive map for all art experiences. B. Results of Latent class analysis identifying 4 distinct experience types, including transformative. C. Core emotional factors for identifying art experience types (Transformative pattern in red).

Network modeling—A basis for understanding and discussing encounters, and transformations, with art

In the present program, we will go even further and add one more key method— employing new techniques for advanced statistical modeling to create detailed mapping of the interconnection of factors in art experience, verifying experience types, and which can provide a comprehensive basis for our further understanding, art applications, and analyses.

This involves constructing a state- of-the-art partial correlation network model of the relationships between the individual factors collected via self reports (Epskamp & Fried, 2018). The interrelationships between the items can also be visualized, allowing the intuitive presentation of the entire “art experience”. Recent extensions of this approach (using piloted Bootstrap Exploratory Graph Analysis, bootEGA; Christensen et al., 2018, and a community detection algorithm, Pons & Latapy, 2006) go even further, allowing for identification of specific communities of self-reported items within the network structure that represent dimensions similar to those in a factor analysis. Consequently, we can identify “core” items within each community (via hybrid centrality measures, Christensen et al., 2018) that are most important for explaining all responses of common-community factors (i.e., “anger” might be a core emotion, with a common community, also explaining how participants will report “disgust,” “anxiety,” etc.). By assessing the answering patterns for core factors across all participants with a technique called latent class analysis, we can identify the specific art experience types held in common by all perceivers and thus providing an empirically-grounded method for identifying the range and the nature of our interactions with art.

A preliminary network model approach has been employed by UNIVIE and partners (e.g., Pelowski et al., 2018; Pelowski et al., under review) most recently with 300+ participants in the Albertina from three artworks, selected to provide a range of positive/harmonious (Claude Monet), conceptually challenging (Gerhard Richter) and negatively-valenced (Anselm Kiefer) art types. Although still only a pilot study, this identified four distinct experience profiles, largely fitting model hypotheses—highly negative, facile/emotionless, harmonious, and transformative/insightful. Importantly, comparison between experience types, which themselves can be assigned, based on the unique answering patterns of core emotions, to individual art perceivers, also showed important differences in changes in mood, liking of the art, overall enjoyment, and willingness to pay to see the art (the latter three were specifically pronounced in transformative cases).

In the first step of the ARTIS project, we will employ the above techniques across a large representative range of artworks and perceivers in settings across our European partners, and testing art in both museums/galleries (WP2) and public spaces (WP3), in order to provide a, first ever, baseline understanding of the distinct finite types of art experiences that can be had and reported. This technique will also produce powerful tools such as a short list of key identifying factors that can be used in future art interaction assessments.

Specific changes and implications of experiencing art

In tandem with the establishment of a baseline understanding of the types of experiences, we will also empirically record specific measurable changes that the combination of perceiver, artwork, and experience type bring about. The primary method for this assessment will be through the use of paired pre- and post-experience measures, such as survey or standardized psychometric batteries commonly employed in the social sciences, and previously piloted in the above UNIVIE studies. These will be carefully selected to target the full scope of main implications noted for the personal and societal implications from art. Measures will include, for example, mood, subjective happiness and well-being, self- identity, as well as valuation and art seeking behaviors (desire to revisit a museum or engage other art).

This approach will itself also be highly collaborative and multidisciplinary, combining several consortium partners’ expertise and previous studies on, for example prosocial attitudes, stereotyping, state empathy, understanding and attitudes in relation to marginalized groups (UNIVIE, see Pelowski et al., 2018; HUB), which, when tied to specific artworks or experience types, will provide measurable answers to art’s role as an agent of social transformation. We will also consider assessments of political outlook or attitudes towards political styles and types of leaders (RHUL, Tsakiris et al., 2019), also identified as robust means for identifying transformation or change as a result of art viewing. The empirical frame will specifically allow us to connect these results to the types of art experience, identifying when and in which measurable ways art can be most impactful. We will also follow-up our analysis at a later date, revisiting a selection of participants either in person or using online survey methods to re-administer the same batteries at 2 or 4 week intervals to assess whether a specific experience on a given day might have any lasting impact on behavior or persons. The above network model approaches and cluster analysis can also be used with time-series data, detecting communities of people who share a similar dynamic pattern (e.g. where the relation between mood, prosocial attitudes, etc. change in the same way from pre to post- art experience.

Personality, sociological profiles or other factors modulating who has certain types of experience

The above results will also be matched to a wide range of micro-level characteristics of perceivers, by mapping out the demographic and individual-differences. As part of our general empirical investigations and interviews, we will collect a uniform dataset using a number of self-report batteries employed by our research partners. This will include variables such as arts engagement, artistic interest and knowledge, gender, socio- economic status, education level, personality traits, sociological classifications of hobbies/tastes, cultural and creative activities (e.g., Stano & Węziak-Białowolska, 2017), to establish the unique backgrounds and contextual aspects of the viewer and identify potential aspects that may increase or act as barriers to experience type.

Top-down identification of “transformative” artworks or those addressing societal challenges— do these actually produce meaningful results?

ARTIS will also match the above baseline with a specific series of investigations of particular works of art that are identified or expected to match this H2020 call (“have generated new thinking, engagement and action in relation to contemporary societal challenges as experienced in Europe,” WP2-3). We will work with our project partners (particular experts with research foci specifically on this topic, Oxford University, Ruskin School of Art’s Drs. Gardner and Hegenbart who have written extensively in this domain, RHUL Warburg Institute, see WP1) to identify examples—within museum/gallery or urban installations. We will also work with our collection of collaboration partners (see Table 2.2.1 below)—e.g., the artists/art consortiums Alexandra Pirici, Studio Olafur Eliasson, Tino Sehgal—who themselves have produced works, noted in the introduction, as recognized examples of societal-challenge-focused major installations across Europe.

These too will be tested at various locations across Europe, with results matched to the above baseline. This will in turn allow us to quantify, against the range of baseline examples, whether the selected works are particular impactful, providing important feedback to policy makers and artists. We may also use a data-driven method, looking at the results of our baseline selection of artworks (also selected by entire consortium), for other compelling transformative art.

Beyond surveys to a multi-perspective nuanced understanding of art experience

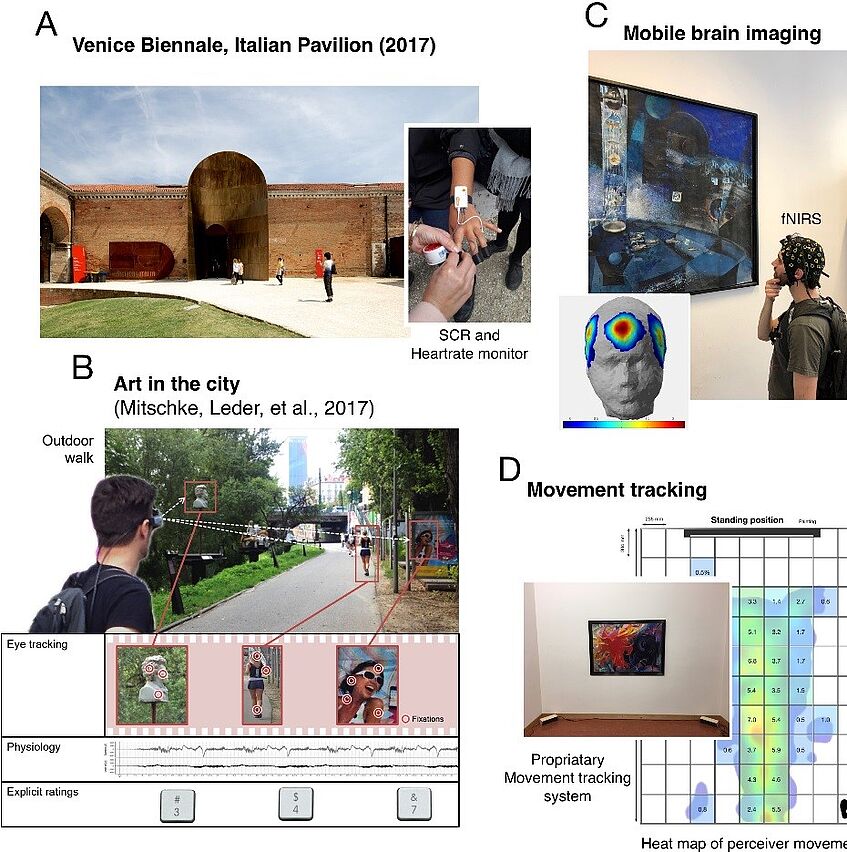

Fig 6. Physiological and movement measures. A. Previous physiological assessment in Venice Biennale. B. Mobile eye and physiology tracking with urban art. C. Mobile brain imaging. D. Movement tracking and results general art engagement heat map.

Beyond surveys to a multi-perspective nuanced understanding of art experience

Although the self-report method is a powerful tool for the systematic exploration and quantification of art experience, we will also couple the above assessments with a number of other approaches, with the goal of producing the most nuanced and data-rich understanding of art experience.

Physiological measures

We will employ advanced methods for matching experience types and artworks to other physiological measures. These may include skin conductivity or heart rate, recorded from small devices worn on the hand or around the torso. These will supply both another channel of information that might be tied to experience types or specific artworks, as well as a measure of specific changes that may be a result of the experience. These too have been piloted by the ARTIS members (Gerger, Pelowski et al., 2018), for example recently in the Venice Biennale, Italian Pavilion (Markey, Specker, & Pelowski, 2018).

Assessment of physical actions and “modes of engagement”, eye/body-tracking, 4E Cognition

We will use interaction analysis/tracking of individuals as they move and engage to consider the relation between individual and artwork body and actions within the interaction space in order to answer what physical aspects of the space and bodily/subjective experience relate to experience types? This will employ a set of methods also verified by our partners in empirical psychology, including use of mobile eye- and body- tracking. In the former, before engaging a specific work, participants are fit with special sets of glasses and small smartphone-sized transmitter worn on the belt and which can use a set of cameras aimed at the area of visual focus and at the pupil to determine the length and target of eye fixations allowing us to map where individuals are looking. Such fixations can provide an important measure of interest, aesthetic appreciation, or emotional experience. This was previously employed by UNIVIE (Pelowski et al., 2018) with a set of installation artworks and showing evidence that participants who experience certain model outcomes exhibit different looking patterns. We also will follow up on theories and empirical assessment.

We will employ methods for tracking movement. This can be done using either a trained rater with a diagram of a gallery space and a checklist of key actions or other factors, who can create maps of engagement for a set of viewers. This procedure was employed by UNIVIE to, for example, investigate social interactions as individuals moved around art (Pelowski et al., 2014). In addition, we may employ new methods such as a wrist-worn GPS/accelerometers, as well as a technique created and piloted by our team, using infrared lasers placed against a wall and which can create a heatmap of movements before a particular installation or painting. This has shown, for example a relation between how individuals move or their viewing distance and their relative artwork ratings. It may be vital in considering the topic of modes of engagement and how these relate to specific varieties of experience.

Subjective experience interviews (Microphenomenology).

We will also employ semi-structured interviews, following techniques from Micro-Phenomenology (HUB and AAU), to further explore subjective experience had when interacting with art, and which might be related to types of experiences as identified via the above methods. This will provide an important counterpoint to the above self-reports or other quantitative methods, seeking for overlap or important differences or aspects previously overlooked. We will also consider artworks/exhibitions/curator and dissemination practices. This will map different types of aesthetic preferences and related interaction styles with artworks / institutions and identify correlated spectator types (regarding education, cultural background), as well as considering if/how previous experiences may have informed specific outcomes with art.

Mobile Brain scanning

We will also use mobile brain scanning. This will employ mobile functional Near Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS). This method uses light, propagating through the skull to measure relative levels of blood oxygenation in the brain, and thus relative brain activity over a target region. This allows for the continuous assessment of a mobile viewer in walking, upright, ecologically valid interaction. Our approach will be based on methods and expertise by UNIVIE (Liu & Pelowski, 2014; Liu, Pelowski et al., 2016), as well as using fNIRS recording technology supplied by their team. An individual will be fitted with the apparatus before viewing the art. Start/stop times, as well as potential self-report signaling of specific reactions (feeling of transformation/insight, awe, anger, etc.) will be recorded with handheld push-button trigger devices. This will explore the relation of experience types or behavioral, health/prosocial implications to brain response, and also moving beyond analysis of single areas to consider dynamic causal modeling of connectivity between regions (see Liu & Pelowski 2014).

We will further employ emerging techniques designed by UNIVIE to considering art as a bridge between the minds of a viewer and an artist, or even between individual viewers of the same work, considering a perceiver’s ability to identify and even to feel particular emotions as intended by an artist when creating or a curator when displaying art (Pelowski et al., 2018). In a series of previous studies, in which we worked with artists or curators to identify emotion transmission intentions, and matched these to felt emotions as reported in surveys by perceivers, this showed that individuals were routinely able to feel into and share intentions and that these correlated to deeper and more positive interactions with the art. Such responses are also suggested to correlate to increased perspective taking, empathy, or pro-social adjustment (Gerger, Pelowski & Leder, 2017). These implications will be further tested here, also tying responses to fNIRS data targeting main areas involved in emotion contagion, empathy or theory of mind.

Experience sampling and tracking of art experiences in everyday life

ARTIS will also employ multiple techniques that allow participants to speak to us about their art experiences without presuming when, where, and with what these engagements occur, and capturing how art is encountered and what types of experiences are had in the everyday living and working environment.

Mobile smartphone-enabled experience sampling and geo-mapping of art engagements

We will use an experience sampling technique to track art or general ‘aesthetic’ experiences throughout the everyday lives of participants. This makes use of special apps that can be downloaded onto an individual’s mobile smartphone (Cotter & Silvia, in press). Throughout a testing period of a few weeks, individuals receive periodic prompts throughout the day for many days, answering questions about their immediate thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and the environment, or about what has happened since a recent interval (have you seen an artwork in the last hour?). This technique has been used to examine, for example, how often people work on creative tasks (Conner, DeYoung, & Silvia, 2018), how mood relates to engaging in creative activities or to study music listening in daily life (Juslin et al., 2008), among many other topics.

Here we will employ this to inquire about individuals’ recent art or aesthetic experiences, if any, with follow-up questions regarding key emotion and cognitive aspects (based on the short list from our baseline studies) allowing for the systematic identification of experience type, and matched to other questions such as type of object, well-being or attitudes about others or oneself, providing answers to: (1) What kinds of ‘art’ do individuals actually report, and how do individuals use or respond to aesthetic experiences throughout their lives? (2) What artforms and specific examples they most engage with and what they find most compelling or personally important? (3) What types of experiences they are having—Are fulfilling encounters outside institutions actually transformative or do they align with other experience varieties? This will also allow for identification of transformative or other aesthetic experiences that may not be picked up by cultural institutions and that occur outside of a formal art context, and at the same time also provide important information on enjoyment barriers or other interpersonal or intercultural differences. The APPS can also track (via GPS) the location wherein individuals had experiences, creating maps of important art experiences, or even transformations, across the cities or countries where we will work (WP2,4).

Online survey of individuals’ most meaningful or important lifetime art experiences

We will also continue to utilize an ongoing program (The Art Experience Archive Project) for collecting, comparing, and sharing individuals most important lifetime art or aesthetic experiences. This was conceived as an additional answer to the longstanding need to begin systematically collecting data on profound art interactions in order to answer outstanding questions in both psychological science and the humanities in order to create a platform for soliciting and carefully recording profound or important accounts, and which will provide one more channel of important information for stakeholders and scientists in order to address the following questions: What factors constitute our most profound art encounters? What patterns or varieties of responses can be discovered in between-subject comparison? What demographic or contextual factors contribute to varieties of experience? These results can serve as an important counterpoint to the empirical museum/city data, comparing experiences had with specific artworks to individuals’ most profound events, and will also allow us to identify what types of stimuli, media, artists are the most affecting, or how varieties of experience might differ between countries or types of viewers. We will also explore differences between country/art type/museums, to identify those aspects which show high importance to evoked profound or negative/positive experience (WP4).

Assessment of the work of artists; Social, cultural, and political aspects of arts engagement

Running in parallel to the above empirical assessments of the end-perceiver or ‘user’ of an artwork, we will also devote specific work packages to exploring other stakeholders and the wider social and political context wherein art is perceived and created.

Interview, Focus Group, Workshops

We will employ a range of inductive methods (bottom-up), such as semi-structured interviews, to unravel artists’ motivations for making art and to understand whether the artists’ potential to make a lasting impact depend on socio-cultural factors, working with professional artists and art students or educators in our consortium and wider collaboration networks. This can answer important questions such as if certain motives or other background factors lead to a desire to make transformative art or to address social challenges, or even lead to more impactful art outputs. Although literature suggests that knowing about the artists’ motivations for making art helps people to understand and give a fit judgement about the piece of art, we do not know what kind of motivations enhance the artists’ impact (Preissler & Bloom, 2008; Barrett & Jucker, 2011). This will also compare between artists from differing socio-cultural perspectives—with different motives for making art that may involve preserving or changing societal structures. This will help us to understand how artists engage with wider society, will shed much-needed light into how socio-political structures use, dissuade, or make space for transformative artists.

We will also consider the very topic of transformation and the H2020 call (“generate new thinking, engagement, action…”) in relation to contemporary societal challenges in Europe. By having artists from the beginning of the ARTIS project as collaborators, we will create valuable input and information that can help shape all of our investigations.

We will also use focus groups to generate critical and deep knowledge that is usually less accessible in an interview. The ARTIS project will assemble focus-groups that consist of different stakeholders involved in the production and promotion of art: artists, curators, art critics, etc. (Lambert, & Loiselle, 2008; Kitzinger, 1995). The advantages of the focus-group method is that it is sensitive to cultural variables, it fosters the discussion of topics that are seen as taboo in a particular setting (e.g., making art with a “political agenda” rather than making “independent” art) (WP5).

Ethnographic assessment of the art-making process

We will extend the above interviews by using ethnographic documentation of the actual working process held by artists in European countries that differed in the type of incentives promoted by the state. The comparative examination of European countries that differ in their economic development and political background (e.g., Serbia and Denmark) will shed much-needed light into how socio-political structures use, dissuade, or make space for transformative artists. The qualitative data that will be analyzed with the Grounded Theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), will give rise to a testable theoretical model. The theoretical model will also include a taxonomy of artistic motivations that will be categorized along several dimensions (e.g., prosocial vs. self- focused motives; politically engaged vs. disengaged), and which may be employed in interventions with perceivers of art to modulate reception and impact.

Multilevel secondary analysis of survey data -Tastes, personality and inclusive identities

We will also investigate differences in the production and reception of art via multilevel analysis on our survey data collected from participants. This will include both the micro-level characteristics explored above, and compared to other European countries using online panels that include representative samples (e.g., ProlificAcademic, ResearchNow, etc), across diverse geographic areas of Central Western versus South and Eastern Europe, identifying individual-level variables that might be matched to different experience types or visitors, as well as identify social context and barriers to engagement.

We will also investigate how artistic engagement relates to societal (macro-level) characteristics that may promote or obstruct community resilience in Europe. This will involve comparing our art viewers’ profiles to, for example, the European Values Survey (EVS), a longitudinal, cross-cultural survey carried out across all member states of the European Union, and including measures of engagement in artistic and cultural activities,

as well as measures of political trust, social inequality, social cohesion, attitudes towards immigrants, attitudes towards democracy, and feelings of belongingness to the EU as a supra-national identity.

This will be the first large-scale cross-national study in which individual-level variables, country-level variables, and their interaction will be considered in tandem to map the relationship between art and community resilience. By comparing our sample of participants we can identify commonalities or key differences that may coincide with geography or sociopolitical factors which may be crucial in crafting interventions or policy, and creating a map of “transformative seeking” or “high/low transformation-potential” viewers and artists, addressing the aim of considering “motivations, philosophies, local/regional/national identities”.

Theoretical and art-historical embedding and connections of empirical approaches to wider discussions on the arts and science

We will also actively use methodologies to bridge the gap between empirical results and theorizing in the humanities on the relation of artworks. This will be achieved in the course of the specific expertise of HUB (Berlin School of Mind and Brain), which has several members specifically focused on uniting and finding commonalities between the humanities and the sciences, and in repackaging discussions or data so that it may be most actionable for members from different academic and societal areas. This may take the approach of questioning our empirical methods, discussing their potential and limitations; comparing the explanatory value of different empirical, philosophical and historical approaches; and considering normative arguments for the utility of art. We will also provide theoretical background on recent discussions regarding particular tendencies to define art as useful and its impact as measurable (e.g. Arte Ùtil, Wochengruppe, Forensic Architecture). This will also help to avoid reductionist tendencies in interpreting the data, providing, feedback on experimental designs and research questions.

Our consortium members in art history and theory (UOXF, RHUL) will use methods (investigation of secondary and primary sources, consideration of the interviews/empirical data) to identify trends in the development of art, situating art’s role in society across differing contemporary or historical examples.

Experiments or interventions with participants

Throughout our main data collection stages, we will also employ experimental methods to more directly compare and assess specific factors, questions, or interventions. This may include, for example: a proposed test of the effect of various motives for making art on the audience’s artistic judgments (WP5), presenting participants, either in the museum or a lab, contemporary artworks together with different background information on the artists’ motives. This may test how the audience responds to art that is driven by certain motives (i.e., creating beauty, working for money, desiring to change ideas or social viewpoints), as well as how the wider socio-cultural context of the artwork and audience color responses? A similar study may be conducted in museums, and focusing on specifically transformative art. This is based on published work (and recently used with art by UvA) showing that providing visitors with an explanation of artists motivations can help them to engage and enjoy transformative experience (Newman & Bloom, 2012). These tests will be refined and actively employed in our final work with artists to maximize the impact of their works.

Co-creation and co-experimentation with artists

We will take the empirical data on viewers and artists, as well as our consideration of social, political, and cultural implications, and actively apply this knowledge in collaboration, co-creation, and co-experimentation with artists. This will involve a series of workshops, lectures, visiting artist discussions, meetings with gallery or museum directors and other stakeholders to actually create and explore art production or interventions that address the stated H2020 aim (“thinking, engagement, action…”). This is described in WP8, and will work within KHB, with the outputs of this work exhibited in Berlin, and followed by a similar program in Belgrade (FDU), and using these as one more empirical test-bed for co-experimentation with the artists related to investigating the impact of art, and exploring viewer- or context-centered interventions on reception.

Inclusion of Marginalized and Disengaged groups

Fig 7. A. *foundationClass (KHB). B. SAVVY gallery, Berlin.

Inclusion of Marginalized and Disengaged groups

Throughout all project components, we will also specifically engage mainstream, art-disengaged, and marginalized groups (see Concept 1.3.1 above). Whereas the mainstream can be engaged spontaneously as they themselves encounter our target artworks, the latter groups will be actively sought, bringing them, if necessary, into the institutions or street locations so that we might record and assess their own experiences. In our onsite empirical studies, this will includes working with our external stakeholder partners or existing relationships throughout our testing communities to identify individuals and bring target individuals to the same institutions, quantifying their own experiences using our same methods and comparing types of experiences, as well as key psychological processes and factors that occur. We will also identify structural or personal differences that must be addressed. In our experience sampling, we will target again both individuals in the mainstream society of our target cities as well as marginalized or disengaged communities. Similarly, we will seek out a comparable balance in our work with artists.

We also have the opportunity to work with collaboration partners specifically focused on marginalized groups or recent immigrants—such as SAVVY Contemporary gallery in Berlin (Table 2.2.1), which addresses its activities to meetings of Western and non-Western (primarily African) artists and using art performance to change xenophobic and racial violence and widening gaps in class and economic realities.

The *foundationClass (Weissensee Kunsthochschule Berlin, KHB)

Throughout the ARTIS program, we will make use of a unique art educational program at our consortium partner (KHB). The *foundationClass (http://foundationclass.org/programme/) was founded in 2016 with the aim of creating a program directed focused on asylum seekers to Germany (20-30 participants) who themselves had been working artists or had gained acceptance into an art school before fleeing their home countries. The program is designed to serve as an introduction and doorway to European arts culture as well as pragmatic issues of artistic careers (preparing portfolios, selling works). Even more, it is itself a radical new approach to art education and application, focused on transformation of art and society itself. As noted in their manifesto, the *foundationClass views art academies as powerful spaces of knowledge production, which, often unconsciously, may (re)produce mechanisms of in- and marginalized groups by creating standards for who makes and receives art. Thus it seeks to question the norms, conventions, and habitus of art institutions and the industry, and creates a space within which skill sharing and knowledge transfer can emerge.

*foundationClass also functions as an ongoing artists’ collective with a collaborative art practice, and has been awarded the “Power of the Arts” prize as well as the DAAD Welcome Prize. ARTIS will embed itself within this structure, integrating with its activities. By working within this course as a constant partner, we will gain unique perspective for our focus groups, interventions and policy deliverables.

Policy investigation and production

Throughout ARTIS, we will work with our policy experts (FDU) as well as societal partners IFNU (and external collaborators and Strategic Board Members UNESCO, ENCATC) to investigate current policy approaches, and actively engage with a wide range of stakeholders and policy makers in bottom-up policy creation and the production of important tools—comparable contextual models, engagement maps, quantified data on art experiences—to take the ARTIS empirical findings and translate this into a form that can make the upmost impact on understanding and shaping art as a vehicle for addressing societal challenges in the EU. (See Section 2.2, for a systematic strategy laid out in the Communication, Dissemination and Sustainability Plan, CDSP, also WP9, Part 3).