Concept

To achieve our objectives, ARTIS is framed around three main concepts that together will drive the project and define the scope of our work: the concept of transformation as a theoretical and scientific focus for investigating interactions with art, empirical assessment as a means of approaching this topic, and a multiplicity of perspectives that we will considered.

Transformations

The central concept for our consortium is that of transformation. Most simply, transformation can be thought of as a synonym for change, referring to the modulation of something in relation to an event. For the purpose of the ARTIS project, transformation provides a particularly useful vehicle for approaching our objectives and for discussing and quantifying the efficacy of art. Transformation as a topic is considered in both the arts and in science, providing a conceptual bridge between the humanities, art theory, and especially psychology.

With respect to art, it has long been argued that aesthetic experiences are transformative by nature. For example, Kant (2000), suggested that in an art experience one might transition from being overwhelmed by a stimulus, to regaining control, and, within this process, changing themselves. In the same tradition, Schiller (1982) more explicitly insisting that art has the power to change the world through its noble images of beauty, morality, and justice that can inspire and educate humankind and transform attitudes to life. For Schiller, one is literally not the same person after an encounter with art, because one has become inoculated with new capacities to deal with challenges. In current art theory, several writers and artists specifically vouch for this topic. According to the currently widely received Arte Útil (2019) program, art has to satisfy the following criteria they list on their webpage: “Propose new uses for art within society. [...] Be implemented and function in real situations. [...] Have practical, beneficial outcome for its users. [...] Re-establish aesthetics as a system of transformation.” They taking concepts like the “total work of art” as they have been reconceived in the 20th century (e.g., by artists such as Schlingensief, Hirschhorn) to a direct assessment of the practical outcome of transformations for our society (Wolterstorff, 2015).

Transformation, as seen in the examples that began this proposal, is also specifically used by art critics, curators, and everyday viewers to describe their experiences, referring again to notable changes in their perception (e.g., Turrell), their conceptions (Abramović), or relations to others (Tate Exchange). Transformation is also specifically used in policy discussions of art/cultural management (Belfiore & Bennett, 2007; Cohen & Heinecke, 2018; Grillitsch et al., 2019), once again to refer to specific effects or adjustments that are sought as a focus of art.

Importantly, especially in the discussion of psychology, transformation is also a topic, which gives actionable frameworks and hypotheses for empirical assessment. Here, transformation is typically suggested to refer to a cognitive process whereby individuals encounter or perceive the environment, and as a result tend to change or modulate something about themselves or experience some modulation of their behavior or bodies. This topic was specifically suggested for the domain of art by Dewey (1950), and in an early cognitive discussion by Lasher, Carroll, and Bever (1983), which related transformations to the process of insight and personal development. More recently, transformations were made the specific topic of a model by our UNIVIE team (the Vienna Integrated Model of Art Perception, VIMAP, Pelowski et al., 2017). This model (see Methodology 1.3.2 for more discussion below) is considered the most comprehensive attempt to organize and explain art responses (Kuiken & Jacobs, 2017). It is also the first to specifically articulate, within this frame, transformative experiences or specific cognitive or behavioral changes as a distinct type of art engagement. The model specified a particular process involving an individual’s prior expectations, or schema, which they would use to guide their actions and thought. These in turn could be applied in the interaction with art. They proposed that in cases whereby an individual would experience a mismatch or a “challenge” to their schema and beliefs, this could lead to a process of, first, attempting to cope or push back, followed by acceptance, reflection, and eventual change of schema or the self, leading to what they considered a “transformative art experience.” This process was related again to insight, personal growth, and change of conceptions. The conception of schema change or affective-behavioral modification at the individual level can also connect to similar discussions in social psychology (e.g., Cialdini, Petty, & Cacioppo, 1981; Gergen, 2012), which notes that cumulative transformative events can shape collective behavior, social or political movements, identity, even culture. Thus, transformation as a focus nicely encapsulates the very changes and implications desired for art research and will be the target using our methods (see Methodology 1.3.2).

The model also embeds transformation with three other outcomes, which provide important counterpoints to considering or comparing transformative experiences. Here, members of our consortium have specifically considered such alternative modes of art engagement. Among them are intense emotional experience such as beauty (Armstrong & Detweiler-Bedell, 2008) or experiences of awe and wonder. Especially the latter has been a research focus of HUB: art often aims at wonder experiences (as do, e.g., the works of our collaborating partner Olafur Eliasson) and wonder entails a mode of engagement (e.g. the widening of the eyes in order to take in more information) that might be conducive to change (Fingerhut & Prinz, 2018). Intense awe as it is experienced for example by astronauts in space flight has led to substantial changes in their outlook in life and their concept of self: many have become more religious after such experiences (Gallagher et al., 2015). Other modes of engagement such as playfulness, addressed by our AAU consortium member, where we engage with a stimulus, other people, or the environment free from rules, may also be transformative in the sense that they allow individuals to take new perspectives or try out new ways of thinking—potentially especially a basis for participatory art (Heimann & Roepstorff, 2018). Importantly, these outcomes have also been connected to the above model, and thus give important comparative varieties of art experience that also may have important effects.

It is also important to consider that transformation does not necessarily imply a positive development. This too can be considered by using the model frame. It is possible that art experience may lead to negative changes. The long history of art as propaganda or its use to support dictators, fascism, or nefarious purposes is a testament to this. Recently, as noted by our UOXF consortium partner who investigated postsocialist art, the artworks considered do not necessarily have positive effects on emerging democracies (Gardner, 2015). It is important to be mindful of such uses or framing of transformation within different political and social contexts. It is also possible that negative transformations may occur, for certain individuals, without the intention of the artist. Art, or transformative experiences, could lead to outcomes that are not socially desirable. For example, another outcome of astronauts’ space flights was higher rates of divorce. Certainly, post-traumatic stress disorder or other negative effects of war—described by Benjamin (1986) as powerful artworks—suggest that a nuanced understanding of this topic is needed. Of course, it is also important to consider the possibility that transformations may not happen, or that art, especially, may have only a fleeting effect. These potentialities, too, will be considered.

Empirical assessment

In order to address transformations, or the actual scope and limitations of engaging art, it is necessary to employ empirical assessment. Empirical assessment is often thought of as involving the domain of science, referring to the collection of data or the conducting of experiments. However, empirical has a more basic meaning, which constitutes the foundation of this project. For us, the defining aspect of empirical research involves a systematic approach to the investigation of a phenomenon (Kerlinger, 1979). This presupposes a specific process: (a) defining a target that one wishes to investigate, (b) deriving a theoretical basis or expectations (hypotheses) for what one expects, (c) identifying the factors or aspects by which one can assess this topic, and (d) collecting data on these features which can then lead to actual inferences about the nature or even existence of the phenomenon. By grounding investigation in a systematic basis, this also allows others to use the results for their own ends, building on and further developing our work. Thus, we can move beyond assumptions or anecdotes and arrive at a cumulative knowledge regarding the possible efficacy of art. Such a systematic and actionable way of investigating art has been especially called for by multiple stakeholders in the field of art. Belfiore (& Bennett, 2007), our external advisory board member, has put it this way:

“whether in education or in society at large, the belief is the same: ‘the artistic experience can have transformative effects on both the individual and society’ The challenge at both levels is also the same: to explain exactly how the arts operated their magic upon people; by what mechanisms the arts were capable of leaving a life-altering mark on the human psyche; and what aspects of the aesthetic experience were likely to play the major part in determining or shaping the impact.”

The ARTIS project is therefore designed around a systematic approach to these questions. We therefore use methods developed in specific areas of neuroscience, psychology, and other social sciences which have been specifically tailored for the empirical investigation of art. First and foremost this includes a new approach for using the model hypotheses for specific factors that may delineate events, in conjunction with advanced statistical modeling (see Methodology 1.3.2.1).In addition, beyond mere systematic analysis, we aim to be comprehensive. One particular approach, or measure, often due to the very need for a controlled, systematic analysis, also has limitations. It might also provide evidence that is contrary to other approaches.

By combining measures and expertise, we will directly address this. This is especially necessary because philosophy and art history have recently also worked more and more experimentally. We will incorporate philosophical approaches regarding the role experiments could play in aesthetics (Cova & Réhault, 2019), in order to be comprehensive in our approach to empirical sciences.

We also argue that empirical should not be reduced to only quantitative measures. Philosophy, social sciences, and phenomenology work with qualitative approaches that also provide important evidence. This can especially fill in the gaps between reductive empirical data, while also providing the most expansive, nuanced present understanding of art experience. The need to accompany quantitative data has led to new ways of assessing also qualitative data, which include recent developments such as micro-phenomenology that one of our consortium members (AAU, see methods section below) actively seeks to combine with psycho-physical measures from cognitive psychology

Artworks and the actions of artists can also be thought of as empirical or even laboratories for investigation. This may include both the artist’s work to consider a topic or work through an artistic problem, but also their action to place a work within the world, and therefore change or modulate something. The results of this can and in the ARTIS project will be measured.

Perspectives

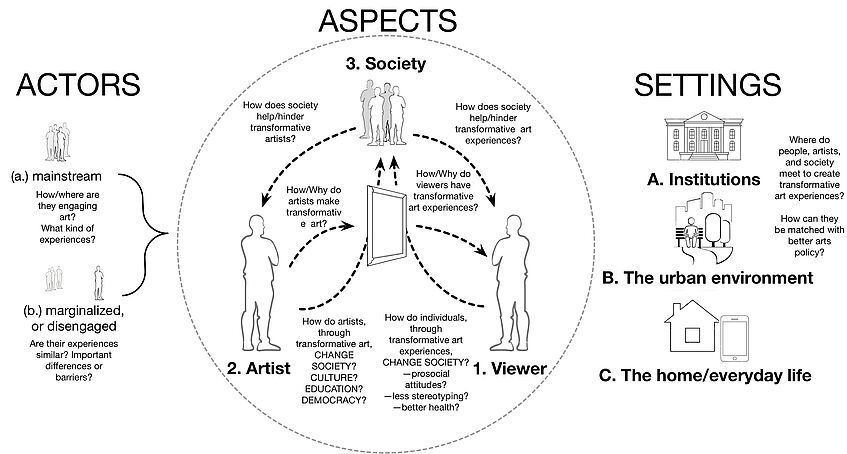

Fig 2. Main Perspectives for ARTIS investigations of art/transformative experience

Perspectives

Finally, for a comprehensive empirical investigation of art-elicited transformations it is necessary to consider several important perspectives (Fig. 2).

Aspects: First, we will address three aspects and levels that are important for art experiences: (1) the perceiver, (2) the artist, and (3) the wider society. Each interacts with art, and through this interaction, those perspectives also impact each other. This raises important research questions.

In the case of the perceivers, it is necessary to address how they are responding to art and of course how and why their experiences might be transformative. At the same time, it is important to connect

transformative encounters to an understanding of art experience in general--what is the scope of possible experiences and how do transformations fit within this realm? This will be addressed in our work packages by theoretical models by UNIVIE, which specifically suggest the transformation varieties alongside other non- transformative experiences. In order to provide a truly comprehensive understanding, we must also consider art experience that can be addressed at the level of cognition, emotion, physiology, and modes of engagement. Are certain ways of moving around art related to a specific type of response (Seidel & Prinz, 2017)?

Behind every artwork is an artist. We might ask how or why artists make transformative art, or whether they consider this to be a viable topic. To our knowledge, this has never been investigated and will be considered by our art school partners in Berlin, Belgrade, and Oxford.

Both perceiver and artist also operate within a context and a wider society. By producing and experiencing transformative art, both may shape and be shaped by society. We will follow social psychology and cultural policy perspectives and ask whether individual perceivers change society. Here, we can use such concrete measures as changes in prosocial attitudes, improved perspective taking, reduced stereotyping, or generally improved wellbeing that might occur through experiencing. Those may have a cumulative effect on society (Cuypers et al., 2012). We can ask the same for artists. Through making transformative art, they may change culture and society around them. Our consortium members (Tsakiris et al., 2019) have shown, for example, that encounters with art, such as depictions in the media of images regarding the refugee crisis, can result in measurable changes in dehumanizing attitudes, preference for a more/less dominant political leaders, or support for pro-refugee policies, as measured on self-report batteries. Similar effects have been suggested for such personality or outlook features such as prosocial behavior, empathy, or perspective taking, which may also be changed as a result of engaging art (Pelowski et al., 2018; Gerger, Pelowski & Leder, 2017).

Thus, these factors, when embedded in our approach, may identify important outcomes of art experience.

One can also ask how society itself may influence the perceiver, or how society helps or hinders the work of transformative artists. This may involve a range of issues from top-down regulations or directives for art making, to decisions regarding funding. Even general tastes held by society members who may respond differently to more or less challenging/transformative-focused works influence what kind of art is produced.

Settings: We investigate art experiences in three settings. First, we consider art in the museum or gallery. These institutional settings represent a typical location for encountering art. They may also be the setting where one expects to have a powerful or transformative art experience. Indeed, surveys of individual’s expectations for visiting art museums (see Pelowski et al., 2017 for review) suggest seeking such experiences. Jansen-Verbeke and van Rekom (1996) found that 25% of visitors had the goal of “learning something,”

followed by “enriching life”. Chang (2006, p. 173) suggested that frequent visitors “value learning,” want to “undertake new experiences,” and place a high value on doing something worth-while with leisure time (see also Falk, 2009). At the same time, the museum may itself lead to certain types of experience or preclude them. For example, the white cube of a modern gallery space might be said to sanitize art or remove it from our everyday lives, making it impotent.

It is important that we consider art both in an institutional setting and as it is encountered in urban spaces. The latter setting represents an important counterpoint from the art institutions explored above, with artworks that are typically accessible for free and encountered in an everyday context: walking through the city, shopping, going to work. Thus, art may be encountered by a wider range of visitors. Architecture itself might be experienced as art. Art in urban settings is often installed and funded by government or private agencies or private galleries. It may also be implemented without such an institutional backing, think of pop- up installations and graffiti. As such this represents an intermediary between an institutional art context and what is called everyday aesthetics. How are these artworks experienced? How do those experiences match to those encountered in the museum? What is their impacts on attitudes, health, and behavior?

The urban/city location raises further questions regarding how encountering these pieces spontaneously might modulate everyday life routines or activities. Taking a more expansive view of art’s typical definition, we might also compare and contrast other urban designs and monuments such as fountains, parks, and architecture, which may also be considered.

Art is also often encountered in more personal settings, such as in the home, one’s religious building, or one’s office. These encounters, too, are not rare. Rather art is an omnipresent element of interior spaces. Pieces collected and displayed by an individual presumably were also chosen because they were meaningful them or had led to strong reactions (Csikszentmihalyi & Halton, 1981). Thus, these may or may not also be a compelling vehicle for transformation. It is also important to ask what artforms and specific examples individuals most engage with and what they find most compelling or personally important? What kinds of ‘art’ experiences do individuals actually report when they are asked? What role do aesthetic experiences play throughout their lives. All three levels will be considered in the ARTIS project.

Actors: Finally, ARTIS considers the ‘who’ underlying art engagement. How one anticipates, responds to, or even decides to encounter art is of course tied to a large number of interpersonal factors—personality, previous experiences, training (Leder et al., 2012; Pelowski et al., 2017). It is necessary that these aspects be considered, especially in shaping policy in regards to who seeks out, has, or enjoys transformative experiences. Understanding the impact of art on the societal level also relates to larger questions such as who has access to art and culture, what impact does art have on activism and politics, and what roles do artists play in the societal dynamics. Here, we will focus on three groups: (1) so-called ‘mainstream’ members of art society who do engage art—i.e., those individuals who we might encounter in studies within museums or urban areas, as above. Studying these groups is of course important for understanding how a majority of “art users” are actually encountering art, and also what is the present efficacy of artworks. At the same time, throughout the ARTIS project, we compare against (2) more art-disengaged groups. These individuals may choose not to seek out art, visit museums, or may not enjoy art (Hanquinet, 2013). Thus, it is important to consider why this may be, or if these individuals are equally as susceptible to transformations or adjustments via art. (3) We will also consider marginalized groups. In this case, we focus on recent immigrants or active asylum seekers. These individuals may have similar or very different relationships with art, and especially the topic of transformation. These individuals are asked to integrate as new vital members of European culture, and also themselves, through their addition of new perspectives, traditions, artforms, or experiences are helping to shape the culture around them.

Thus, within this program, we will consider these groups, by, for example, bringing individuals into the same institutions to engage the same art, and comparing their experiences. This will be vital for identifying important barriers or even commonalities in experience, or identify other relationships or uses of art and transformation.

Our chosen cities also provide a balanced perspective of both immigration and socio-political aspects. According to Eurostat, all capital cities that are included in our consortium (Amsterdam, Berlin, Copenhagen, London, Vienna, and Belgrade) are major immigration centers. London is the most cosmopolitan European city with more than one third of its inhabitants being born in a country other than the UK, and Berlin ranks among the top 3 immigration centers in EU with 652,000 foreign-born inhabitants. Although all six cities are similar in terms of being immigration hubs, they differ on two important aspects: how open the local

population is to migrants and where their migrants are coming from. While some cities attract the majority of their migrants from a narrow range of countries (e.g., Vienna from Serbia and Turkey, and Belgrade from Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo), others are extremely diverse, drawing migrants from all over the world (e.g., Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and London). Concerns over the contribution of migrants in these EU cities do not necessarily increase as the share of foreigners in the total number of inhabitants rises. On the contrary, cities like Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and London display a diversity and fusion of cultures and arts that create more room for integration. Differences in the origin and integration of immigrants in the cities that are part of the ARTIS consortium create interesting opportunities for comparative research that we aim to tap into to understand how the integration of immigrants through art can increase the beneficial outcomes (e.g., economic prosperity, faith in the EU identity) for both the host and immigrant populations.

The above perspectives can also be considered at the stakeholder level—artists, educators, museum officials, those interested in social or political perspectives—delineating the various interests and questions that each might have.

Technology readiness: As described in Methodology below, the approaches we will use to unlock the above aspects, and to engage in empirical analysis, are at an advanced stage of readiness—TRL4 validated in lab, or TRL5 validated in the field, such as a museum of art. Here, they will be combined and our scope greatly expanded.